In November 2012, I wrote a brief essay about my plans to teach my United States history survey backwards—by starting in the present and working my way back to 1848. I have since taught this “backwards” survey twice in slightly different forms, most recently in the Spring 2015 semester. And I have also received a number of emails from curious readers asking what I have learned.

The short answer is that the experiment worked, or at least worked well enough to warrant continued trials. By organizing my course in reverse chronological order, I hoped that students would be more engaged, though I also feared that they might be more confused. In most cases, the hope proved better founded than the fear. In the responses to an anonymous survey that I gave my students this semester, three quarters of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the “backwards” structure increased interest, and when presented with a choice of four things they would change about the course, only one in five chose to go back to the usual chronological order. One Spring 2015 student commented that the new structure “made studying history feel more relevant to my life now,” which was music to my ears.

These are unscientific measures, of course, but I have found such feedback from students encouraging. Not all the early results were encouraging, however, and I still have lots to learn. Not surprisingly, my first offering of the course was much less successful than the second. But more surprisingly, the successes of the second offering had less to do with the “backwards” order than I would have predicted.

In what follows I’ll try to explain what I mean, though I’ll violate my own “backwards” strategy by writing in chronological order, beginning with an overview of the Spring 2013 course—Take One, if you will.

Take One: Spring 2013

My first version of the course was especially inspired by a first-week exercise that Annette Atkins uses in her backwards survey. On Day 1, Atkins begins by asking students to “list 10 issues that most concern them,” and then to “read the last chapter of the textbook.” On the second day, Atkins works with students to create a collective list of “issues.” Over the next several meetings, the class begins to think about their “issues” in light of the last 20 years of American history, noticing relations between the two and beginning to develop questions about the historical context in which we ourselves live.

In 2013, I took that idea and ran with it—to a fault, as you’ll see below. On the first day of class, I asked students to make a list of “issues that concern them.” We then arranged the list so that the issues most mentioned were at the top. Here were the top 10 from a list that ran to two double-spaced pages:

- Gun control / guns / gun laws / guns in schools / shootings (x10)

- Equal rights / gay rights / same-sex marriage / redefined family (x9)

- Debt ceiling / debt crisis / fiscal cliff / taxes (x8)

- U.S. world role / distinctiveness / foreign policy / Middle East (x7)

- Party system / third parties / 2012 election / partisanship and gridlock (x6)

- Legalization of marijuana / war on drugs / drug abuse (x5)

- Death penalty / crime / incarceration (x3)

- Immigration / immigration policy (x3)

- Women’s reproductive rights / abortion (x3)

- Technology / dependence on personal devices (x3)

Either in that class or the next one, I then introduced students briefly to the Five C’s of Historical Thinking. As homework, students were required to go to a Google Doc and generate historical questions about the issues we had listed.

I recall the results of that assignment as bracing. They revealed just how much I had typically taken for granted about how my students approached a history class. Many students asked questions about what the future held. Others focused on asking about what the United States should do about a situation—questions whose answers may be informed by historical reflection, but which are not the questions historians typically begin by asking.

In retrospect, maybe the default questions my students asked shouldn’t have surprised me. As Mills Kelly notes, many students “believe that history regularly repeats itself—so if we just pay close attention to what happened in the past, we will know what to expect in the future.”1 Simply by asking my students to give me some questions, I learned that I could not take for granted that they knew what a historical question was, much less that they could think like an historian about the question. Right away I learned that I would need to teach explicitly the kinds of questions historians ask.

Unfortunately, that was the sort of teaching I had prepared the least to do. I did spend the next two class meetings or so talking in greater detail about the “five C’s of historical thinking.” I hoped this would help students to see how they might reframe their questions as historical ones about causation or change over time. By the second week, we had whittled a massive brainstorm of questions down to a more manageable list that was also more historical in orientation.

The problem, in retrospect, was that I had planned for the rest of the semester to evolve from the questions on this list, instead of from a schedule prepared by me in advance. I made the radical decision to put students in the driver’s seat this semester. As I imagined it before the course began, I would be like the driving instructor sitting to the side—coaching students, putting on the brakes when necessary, occasionally taking the DeLorian’s wheel. But students would drive the course forward—or backward, in this case—by deciding which questions they wanted to pursue. I would be Doc Brown to their Marty McFly.

My plan was to follow a routine schedule every week. Before coming to class each Wednesday, students would read a group of primary sources that I hoped would help us reflect on the big Question List we had generated, as well as to generate new questions to add to the list.2 These primary sources would get progressively “older” each week. On January 23, for example, we had sources from the 1990s, followed the next week by some sources from the 1970s, and the next week by sources from the 1950s. You can see all of the readings we did on the course website.

After reading the weekly set of primary sources, and before class began, students would complete what I called Wednesday Reports, one-page assignments composed of three simple parts. In one part, students could pick any unfamiliar detail or concept from the sources and do a little basic Internet research to report on it. In the second part, students identified one of the Questions from the list that the week’s sources could help us to answer, and discussed why they thought so. Finally, students used the sources to propose a new question that we could add to our list, where it could serve as fodder for future Wednesday Reports. By the end of the semester, we had a lengthier Questions page whose evolution can be tracked through its revision history.

Classes on Wednesday centered on discussions of the Wednesday Reports, parts of which students had shared with the entire class on a wiki discussion page. (Click the “discuss” tab on any of the readings pages on the course website to see what these looked like.) In most cases, students worked in small groups to propose candidate questions for addition to our list, and then we typically decided, as a class, which of the questions we were most interested in exploring for the following week.

After each Wednesday class, I left with my work cut out for me. First, I needed to select some primary sources for the following Wednesday that could both address our current questions and push students to think of questions about topics they weren’t considering yet. I prepared a lecture each Friday that attempted to show how a historian might answer one of the questions that garnered student interest. And for Monday, I assigned some secondary source readings (usually journal articles or book chapters) in which historians addressed some other question that had come up on Wednesday.

Both on Fridays and on Mondays, my original goal was less to cover everything related to a topic, and more to coach students on how to add complexity and context to their answers and how to identify and understand questions on which historians disagree.3 But after the first week, I had to spend more time than I had expected coaching students on how to ask good historical questions—a task complicated, as I’ll explain below, by the fact that the direction of the course and the depth of their assignments depended in large part on the quality of questions on our big list.

Our weekly routine pivoted around students’ regular encounters with unfamiliar primary sources and aimed at getting them to think about those sources like historians. To assess those historical thinking skills, I designed two midterm exams, each with a take-home essay (one and two) and an in-class portion (one and two), as well as a final in-class exam. All of the in-class exams were essentially like the Wednesday Reports, but with a twist: I gave students a packet of primary sources in class that they had never seen before, and posed questions that required them to analyze these sources using the skills they had been practicing every week.

Interlude

After the conclusion of my first backwards survey, I was pleased enough with the results to want to try again. But hindsight made me increasingly dissatisfied with Take One.

For one thing, while I had hoped (as I explained in my original post) that a backwards survey would challenge teleological assumptions about American history, many students’ beliefs in the inevitable march of progress seemed to remain unfazed. I particularly recall multiple students’ comments when presented with primary sources about late nineteenth-century lynching. Not a few expressed relief that “nothing like that would happen today,” proving in their minds that racial discrimination of any kind no longer exists. Moving steadily away from the present as the semester wore on did not, all by itself, unsettle the familiar assumption that a vast distance yawned between past and present. If I wanted to help students grasp historical complexity and the contingency of change, I would have to adjust more than the chronological order of the course.

At a more practical level, I realized that the radical “choose-your-own-adventure” design of the course required an amount of work from me that would ultimately be unsustainable if I tried it every semester. I’m not averse to the work of course preparation, mind you. But too much of the work required by this design—find a whole new set of primary sources every week, for example—failed to contribute directly to the learning goals that I hoped to prioritize. Indeed, although my intentions from the beginning had been to help students learn to “think like an historian,” and although (as explained above) many individual class sessions discussed this, an honest retrospective tells me that not enough of my weekly workload concentrated on this goal.

This is partly because, in this first go-round, I had trouble truly letting go of the ideal of “coverage” as an organizing principle in my course. The idea of the survey as a comprehensive tour of a fixed terrain of topics, names, and dates is difficult to abandon, even when one is convinced (as I was and am) that what Lendol Calder calls “uncoverage” is more important in an introductory course. Each week, as I considered what we had done so far and which questions students were asking, I found myself worrying against my better judgment about our failure to talk about X or Y.

So, while an angel on one shoulder urged me forward with my goal of focusing on historical thinking, a voice in my other ear usually convinced me to throw students a curveball reading, solely on the grounds that it touched on some canonical issue that Surveys Must Cover. I allowed this voice to convince me that students, without a general textbook or general lectures, would somehow be able to intuit how this new topic somehow connected to the other questions we had been discussing. I assumed they would use the new reading to come up with a Question on their Wednesday Reports that could lead us in the direction I desired.

But since the angel had taken charge so fully of the course design, I had left myself little time in class to provide students with the context necessary to understand the new topics I was much-too-subtly sliding across the plate. Not that this stopped me from trying to provide that context in class, with mini-lectures that too often attempted to rationalize my eclectic selection of sources instead of coaching students through the difficult process of analyzing them. At too many moments in this first iteration, I succumbed to what I consider my worst instinct as a teacher—to react to puzzled looks with ever-more-extended lectures, seldom pausing to ask students why they are puzzled. Invariably those lecture binges would throw us off schedule, crowding out the learning objectives that supposedly mattered most to me. Regretting my in-class lecture binge later, I would resort to another flood of words posted to the website, hoping I could do there the teaching about contingency, complexity, and historical thinking I wasn’t getting to in class. (I couldn’t.)

These weren’t the only problems. I also now believe that the weekly assignments I gave students were inauthentic, repetitive, and insufficiently challenging. In the beginning, I intentionally designed the Wednesday Reports to be a weekly ritual on the theory that, without the security of a familiar chronological structure, students would need some predictable routines. But the reports quickly became too routine and the students’ answers too predictable. While I had hoped that giving students a significant degree of freedom within the routine would encourage them to be adventurous (they could choose what part of the sources to research further, as well as which of the Big Questions to address each week), the opposite often occurred.

For example, some students learned they could satisfy the first part of the Wednesday assignment with a quick trip to Wikipedia. For the second part of the reports, many selected a question so broad (e.g., “how have ideas about gender changed over time?”) that virtually any group of primary sources could be made to address it. Not a few simply returned to the same question every week, with answers that varied only slightly. And instead of using sources from previous weeks to build ever more complex answers to the same question, Wednesday Reports frequently compared a past decade directly to the present, only to then pass a simplistic judgment about how much had or hadn’t changed. Often these reports only engaged significantly with one of the several readings assigned, which (I belatedly realized) my free-rein instructions technically allowed.

A cynic might lay most of the blame for these lackluster results on the students themselves, but in this case I’m more inclined to blame the assignment. In particular, the greatest weakness in the design of the Wednesday Report was its artificiality: it was a classroom-world assignment created by a professor to be read by a professor, rather than a real-world assignment that students could imagine ever having to complete outside of class. I wanted the backwards course to show students the relevance of the past to the present, but I had designed an assignment that had no clear relevance to the opportunities for historical thinking that students were actually going to experience in their day-to-day lives. In short, given the inauthenticity of the reports, it’s no wonder students treated them as checklists to complete in an incurious and cursory way.

Students were not only unmotivated, but also unprepared to do the work that I was assessing. Aside from my brief introduction of the “Five C’s of historical thinking,” I did little in the opening weeks of the course to train students about how to read primary sources (even though, in my other courses, I devote significant attention to teaching students how to read secondary sources). I did devote time to helping students think about how to frame a good historical question, but because I was embarrassingly ill-prepared for how difficult that particular task would be for survey students, I had to develop a set of criteria for good historical questions on the run.

That wasn’t all bad; because we worked collaboratively on specifying what made good historical questions good, I think the ability to ask better historical questions is one of the main things students left the course with. But because that ability formed slowly in the course, some of the initial, less sophisticated attempts at historical questions remained on the big list that students mined for their Wednesday Reports. Novice work, in other words, exerted an undue influence over the course’s progression, even long after students had become more expert at asking historical questions.

All of this led me to a revelation that should have been blindingly obvious to me from the outset: the structure of my course depended too much on students already knowing how to do the things that they needed to learn. Meanwhile, the Wednesday Reports and exams gave students tasks to complete without a clear rubric that might help them evaluate their own progress as learners. Though I would not call the course a total failure, those two flaws seem to me most responsible for the dissatisfaction I felt after it concluded. I resolved, in the next iteration of the course, to do things very differently, or at least to fail better.

Take Two: Spring 2015

The second time I taught my “backward survey,” I made significant changes to almost every dimension of the course, as the Spring 2015 syllabus shows. And while work remains to be done, I was much happier with the way this version turned out, especially because I believe that what students had learned by the end of the course was much closer to my original objectives for “teaching historical thinking.”

I was particularly encouraged by the responses I received to a survey I distributed in class on the last day of the semester. In the very first question, before students had seen any other part of the survey, I asked them to identify “the most important thing you have learned.” The answers were very close to what I had targeted as the course’s “enduring understanding,” the phrase that Mark Sample, drawing on Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe, defines as “the fundamental ideas you want to students to remember days and months and years later, even after they’ve forgotten the details of the course.” Here are some sample responses selected from the full results:

This semester I learned how to think historically by paying special attention to narrativity, empathy and evidence. The most rewarding part was being able to apply these critical thinking skills across subjects. Now when evaluating arguments or narratives, I carefully consider whether claims are linear/simplistic, developed, and supported by evidence.

The most important thing that I have learned is to understand the multiple causes that produce a historical event. The ability to empathize with multiple perspectives is definitely the key to better understanding how things came to be.

Historical thinking; specifically narrativity. Until this course, I really did think that historical events were widely agreed upon, and that historians would flip through there [sic] list of past events, pull one out that was similar to what was being dealt with in the present, and say “hey look, he shouldn’t do that because it didn’t work before.” I’m happy to say that I now understand that things are much more complex and almost never linear, and monocausal in that way. I also have much more of an appreciation for the work that historians do, and the usefulness of that work in the present.

One of the most valuable things that I think I’ve learned this semester is just how vital it is to not portray historical explanations as monocausal. I never before had thought about applying different theories to something that had already happened in order to look at it differently.

I’ve learned that being a good historian isn’t just about knowing a lot of facts. Instead, it is largely about being able to use historical skills to understand and interpret history in a justified way.

I think the whole idea that history isn’t a whiggish narrative, that events aren’t caused by one particular factor, and that history instead is a dense web of overlapping factors was really drilled into our head over the course of the semester. But, I think the most important thing we learned was understanding these historians complex thesi, and comparing them, and seeing how these arguments changed our perception of current events

How to write a historical narrative considering multiple factors, understanding that there is not one linear explanation for events in history.

The most important thing I have learned in the course is the idea of causation being a dense web. I find it especially important and influential to me because I can apply this idea for everything that happens around me and it changed the way I identify problems. For example, when I was discussing the causes of global change in my other class, I started looking for relationships between already recognized causes of the issue rather than trying to name as many factors as possible.

I learned what historians actually do in a concrete sense. Reading the academic articles to see the types of interpretations and arguments helped to show the process of understanding history.

A greater appreciation for the complexities of historical events. It’s very easy to look at things that happen, past or present and place them within their “sphere of influence” and then place those within the sphere of influence of other things, but now I’ve broken down a lot of that structured understanding.

The fact that students felt they had learned these sorts of things—and also that they identified them as the most important things they had learned—delighted me to no end. And with due allowance for the possibility that this was an exceptionally adept group of students, I also believe that the changes I made to my course design contributed to a more favorable set of student learning outcomes.

In particular, three changes made a big difference in Take Two: I developed a rubric for historical thinking that students could use to assess their own progress; I decided to select the central topics of the course myself and organized the semester so that we returned to the present more frequently; and I gave students assignments that were simultaneously more authentic and more challenging than the Wednesday Reports from Take One. (I also decided to use the open-source textbook the American Yawp, and I made another, even bigger change to the course by doing away with conventional grading schemes. But those are subjects for other posts!)

Rubric-Centered Learning

One of my biggest regrets from the first iteration of my course was the insufficient attention that I paid, at the very beginning, both to training students on how to make basic historical thinking moves and to telling students explicitly about my expectations for what they would learn to do by semester’s end. This time around, I spent roughly the first two weeks on a battery of classroom activities and readings designed to help students analyze primary sources and historical narratives. Under a headline reading, “What Should I Be Able to Do by Semester’s End?”, I also spelled out explicitly on the syllabus which skills I wanted students to work on mastering: narrativity, evidence, empathy, style, and self-reflection.

To make those skills concrete, I used “case studies” in the first two weeks to show students “historians at work.” Topically, these case studies focused on famous encounters between American presidents and black civil rights reformers: the dinner between Theodore Roosevelt and Booker T. Washington; the meetings between Lyndon B. Johnson and Martin Luther King, Jr.; and a White House reception held by Abraham Lincoln in the immediate aftermath of emancipation.

In a couple of ways, this choice of topics supplemented the “backwards” nature of the rest of the course. Students received a quick orientation to several different eras spanning the length of the course chronology (1848 to the present). That helped later, I think, when we were jumping around in time. The topics also helped introduce the theme of connections between the past and the present. When the course began, the portrayal of the Johnson-King relationship in the movie Selma was in the news because of Joseph Califano’s controversial op-ed in the Washington Post. Historian Kate Masur had also just published an op-ed, also in the Post, connecting the treatment of African Americans in Civil-War Washington, D.C., to recent events in Ferguson. Both topics helped me start discussions about how historical reflection might inform students’ thinking about their world.

More important than the specific topics, however, was the opportunity they gave me to introduce students to the skills I wanted them to learn. So, for example, by reading differing accounts of the Washington-Roosevelt dinner by Gary Gerstle, Kathleen Dalton, Joel Williamson, and Deborah Davis, we were able to talk about how and why historical narratives differ, and about what makes one narrative qualitatively better than another. And by reading over the same primary sources that Kate Masur used in her Post article on the Lincoln New Year’s reception, or the transcript of a phone conversation between King and Johnson before the Selma march, students gained early practice in reading primary sources, assessing their credibility, and placing them in the context of larger debates.

Those hands-on experiences in class laid the groundwork for a discussion of the learning rubric for historical thinking that I distributed at the beginning of the third week. In an early class exercise, I posted the rubric text on a Google Doc, highlighted key phrases under each of the first three skills—narrativity, evidence, and empathy—and asked students, in groups, to leave comments on the Doc with historical narratives (like Gerstle’s or Masur’s) from the first two weeks that exemplified the highlighted phrases. (We repeated that exercise several times in the course, and eventually students also had to give examples from their own writing or other students’ writing that exemplified rubric language, which enabled them to practice the fifth big historical thinking skill: self-reflection. Over time, this “annotated” rubric became a resource that struggling students could look to for actually existing examples of successful historical narratives.)

These early discussions also helped me refine the rubric slightly by revealing phrases that were difficult for students to understand and suggesting places where I needed to say more explicitly things I had taken for granted. For example, in an early draft of the section on “narrativity,” I had not included anything to suggest that historians generally provide clear chronological markers when making generalizations or discussing events, so after discussing this with students, I added a phrase to that effect in the rubric’s final draft. At the beginning of the fifth week, I distributed a final PDF version of the rubric, and this rubric subsequently became a benchmark that I returned to often in class discussions and lectures, in my comments on student work, and even in brief videos that advised students on concrete ways to use the rubric.

This rubric-centered approach to teaching and learning was, in my view, one of the keys to the course’s success. In some educational circles, of course, “rubric” has become something like a four-letter word. And rubrics can be damaging to learning if used simply as instruments for making summative evaluations of students and teachers. But in this case, having the rubric to guide them throughout the semester seemed to benefit students. Because the lines of the rubric were numbered, I was also able to refer students to particular lines when discussing their work. And instead of evaluating their own progress in terms of the nebulous concept of “historical thinking” that I used in Take One, students were able to see exactly what that concept meant to me.

Perhaps that is why, judging from evaluations and surveys, many students seemed grateful for the rubric, even if some doubted they could reach what it described as total mastery by semester’s end. Many referred to the rubric in their answers to the “what is the most important thing you have learned” question:

The framework of the learning rubric has been the most valuable to me. Though students practice at least the first 4 skills in some way in all other history classes, it is incredibly helpful, especially for the last skill of self-reflection, to have a clear and concise framework for thinking about the skills on which you need to practice and exhibit. I would definitely agree that the focus on the rubric is more important than a focus on subject material.

Instead of assuming that just because someone with a PhD wrote something that it has to be correct, I learned to evaluate narratives using the rubric from this class. This has helped me to be more aware and alert as a reader and student.

The most important thing I’ve learned this semester is how to come up with a quality historical narrative. This class has showed me that there are many different aspects to a historical narrative, all of which are important in order to be able to come up with a quality narrative. This is something that I learned through the rubric, and once I started making use of the guidelines of the rubric, I feel like my narratives improved immensely.

The learning rubric we had was very helpful, not only in this class, but other classes, as well.

The writing skills from the rubric. Incorporating empathy, narrativity, and evidence into every writing assignment was difficult but very worth while. I feel as though my writing has improved dramatically.

As these comments make clear, rubrics can be useful tools when they are focused on helping students evaluate themselves. One of the comments on the official University evaluation highlighted this point: “I found the rubric to be very helpful because I was able to assess my own work throughout the semester.” And out of 23 students who took my instructor-designed survey, eighteen agreed or strongly agreed that the rubric was “helpful for assessing my own learning.”4

Course Organization

A second set of frustrations with my first offering of the backwards survey arose from my decision, in that version, to move steadily back into the past throughout the semester, driven by questions that students themselves had generated. As I’ve already noted, that design led to unforeseen challenges. Some students were actually less inclined to connect past to present events because we moved farther and farther away from today. Moreover, the questions that we generated in the first week of class and in subsequent Wednesday Reports were often too nebulous to be useful for an introduction to historical thinking. After coaching on how to devise questions that took better account of what students had learned earlier in the semester, the questions became better and more specific. But these specific questions were then, paradoxically, not broad enough to serve as scaffolding for the course as a whole.

Reflecting on these problems, I decided that devising original historical questions and thinking about existing historical questions are two fundamentally different skills for novice historians. My first take of the course revealed that students would be ill-prepared to do the former until they had learned to do the latter. In Take Two, therefore, I came up with four or five major questions that I wanted to focus on for the semester and announced them from the beginning in the syllabus. I also decided that instead of starting the semester in the present and moving continually backwards to 1848, we would begin the discussion of each big question in the present and then move backwards in time seeking answers to that question. After a few weeks, when we switched to a new question, we would go “back to the present” and repeat the process again.

This structure had two immediate benefits. First, we returned more often to present-day events, which better served my original reasons for a backwards course. And as we passed back through eras that we had discussed while treating other questions, I think it gave students more opportunities to apply what they had learned already to that new topic.

Perhaps more importantly, under this new organization, I was able to select questions carefully based on whether they would help students understand and implement the skills described on the rubric. For example, one of the questions we discussed was the recent rise of conservatism, an issue in the headlines because of the historic gains made by Republicans in Congress the November before the course began. By sharing recent historical narratives about the rise of conservatism with students, I was able first to introduce them to a relatively simplistic explanation of the Right as a “backlash” against the Sixties. I then introduced them to other narratives that provided evidence of conservative strength even in the immediate aftermath of the New Deal, usually thought of as liberalism’s moment of triumph. After reading these narratives, many students became convinced that the “backlash” thesis was wrong. But that opened an opportunity to return to that thesis and examine which aspects of it still had merit.

In other words, this question and the historiography surrounding it not only allowed us to discuss a wide range of topics ranging from the 1930s to the present, but also served as perfect springboards for discussions of narrativity (avoidance of simplistic, monocausal narratives in favor of more complex ones), evidence (since different kinds of evidence were used, and since evidence of earlier conservative strength both forced reevaluation of the “backlash” thesis and revealed its still considerable strengths) and empathy (since students encountered multiple historians’ perspectives and also, in some cases, had to work hard to understand earlier conservatives like Barry Goldwater in their specific historical contexts).

A final advantage of my picking the main questions for the course was that it allowed me to weave the topics together, sometimes in surprising ways. For example, one of the final readings I assigned for the course was Heather Ann Thompson’s article, “Why Mass Incarceration Matters: Rethinking Crisis, Decline, and Transformation in Postwar American History.” Students were surprised when several of the big topics we had covered earlier—deindustrialization in the textile industry, the rise of conservatism, race and the urban crisis, and even Lyndon B. Johnson’s Civil Rights legacy—converged in this reading. The article also concluded with a paragraph that exemplified historians’ efforts to push past “monocausal” explanations, one of the key parts of the rubric that I had stressed all semester. This kind of “capstone” reading would not have been possible in the first iteration of the course, and selecting it allowed the course to conclude with some powerful questions about the connection between the past and the present.

Assignments

The final major adjustment I made in the Spring 2015 version had to do with the nature of the writing assignments. In Take One, remember, I had assigned formulaic Wednesday Reports that were due every week, hoping with that repeated assignment to provide some predictability to the course. But the assignments ended up being too repetitive, and weren’t designed in a way that required students to implement the historical thinking skills I wanted to teach.

In Take Two, therefore, I did away entirely with the Wednesday Reports. I did tell students that a writing assignment would be due every Monday. The regularity of assignments remained in place. But this time around, I strove to ensure that these assignments were simultaneously more difficult and more authentic. These assignments included:

- “Mock” letters to the editor of the Washington Post responding to articles we had read, but using material from other readings and skills from the rubric.

- A “mock” letter to the local School Board evaluating the online textbook the American Yawp for its treatment of the rise of conservatism, paying special attention to narrativity.

- A new “sidebar” section of the American Yawp asking and answering, with historical thinking, the question, “Why Wasn’t Your T-Shirt Made in the United States?”

- An analysis of the website, Mapping Occupation, using critical insights from other secondary sources we had read.

- Three new paragraphs added to the final chapter of the American Yawp incorporating a discussion of recent killings of unarmed black men by police officers and the protests of these killings.

- Essays that required students to reflect on their own learning by answering the five questions at the beginning of the syllabus, using concrete examples from readings or (in a later version) from their own work.

- A comment posted to the feedback site for the American Yawp on how to improve the narrativity, empathy, evidence, and/or style of a particular paragraph.

- Revisions of earlier assignments incorporating my feedback.

In-class assignments were also far more varied than in the first iteration, and I frequently used the website Poll Everywhere to gauge how well students were understanding the readings and the lectures.

In comparison with the Wednesday Reports, these assignments proved to be much more effective as tools for helping students to learn and for assessing their learning. The extreme variation in the kinds of writing assignments helped me and the students judge whether they were able to transfer understanding to new contexts. It also required them to practice adapting their writing to new audiences and purposes. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, those audiences and purposes were authentic. It is difficult to imagine a student ever having to create something like a Wednesday Report in the “real world.” But it is possible to imagine them writing a letter to the editor or their School Board. In at least one case—the comment that students left on the American Yawp feedback site—the assignment also had a direct real-world value because it helped improve later versions of this textbook. Anecdotal evidence suggests that such “authenticity” made the assignments more interesting for students, and because they were more invested in the task, the work produced was in general much stronger.

The assignments were also definitely more challenging than the Wednesday Reports, especially since I often required students to improve the same piece of writing through revision. As a result, however, students often reported that the assignments improved their understanding, something I’m not sure I can say about the Wednesday Reports from Take One. As a student said in a comment I have already quoted above, “Incorporating empathy, narrativity, and evidence into every writing assignment was difficult but very worth while. I feel as though my writing has improved dramatically.”

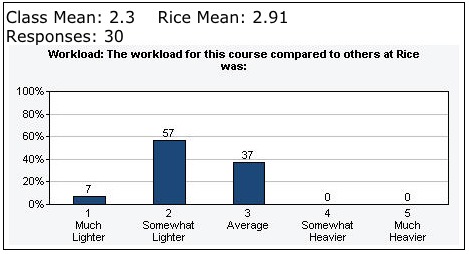

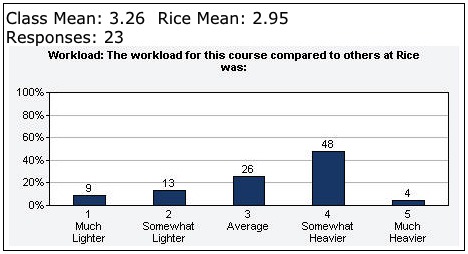

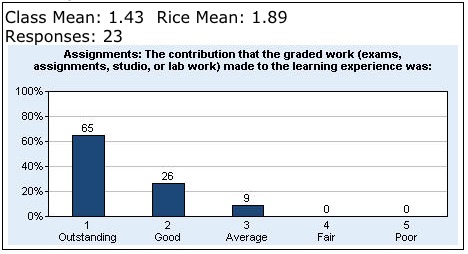

The general statistics on my official student evaluations corroborated comments like this one. Although such evaluations are not always reliable, they can sometimes offer teachers useful feedback on specific changes to a course, as Elizabeth Barre has recently argued. In this case, consider the marked difference in the ways students evaluated the workload for my Spring 2013 and Spring 2015 courses:

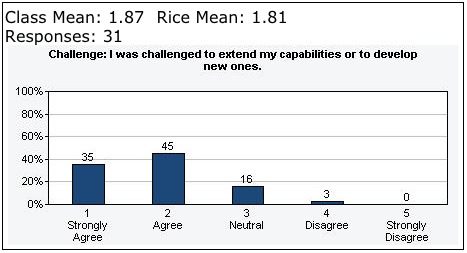

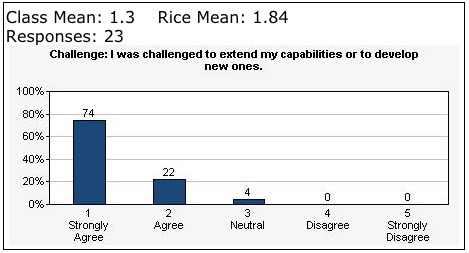

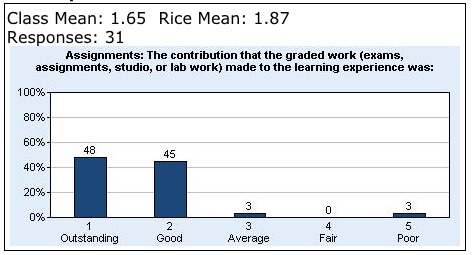

The Spring 2015 workload was somewhat heavier than the average at my institution, but much heavier than my Spring 2013 workload. Similarly, another question on the evaluations suggested that the assignments were more challenging:

Yet despite (or, as I think, because of) the increased workload and challenge of the Spring 2015 assignments, students also reported that the assignments contributed more to the learning objectives of the course:

While further offerings and evaluations are certainly needed to show that these differences were not flukes, they support my own interpretation of what happened in these two courses. And they help to explain why, even though I had not named writing as a primary learning objective in my course, many students reported (on the separate survey I designed and administered) that the assignments helped them hone this skill.

Looking Forward

In conclusion, looking back on two iterations of my “backwards” survey, I think I can draw a few lessons that will help me improve the course in the future. Though my experience may be idiosyncratic, these lessons may also help other teachers determine whether a course design like this will work for them.

The first lesson (as with any new course) is that teachers must be prepared at first to fail, and to accept such failure as necessary to identifying what can be improved. Asking for and paying attention to student feedback can be especially valuable in this essential process of reflection and revision.

A second lesson, which I learned the hard way, is that teachers should only assess what they plan to teach. In my first course, I erred by expecting that students would know, right off the bat, how to ask great historical questions, even though I had not prepared sufficiently to teach them how to do that. In the second course, I was better prepared. But even then, I believe that I gave far more “teaching” time to certain parts of the rubric than others. In future iterations, while I might leave the entire rubric intact in order to show students how complex these historical thinking skills are, I might acknowledge more explicitly that certain parts of the rubric will be receiving more attention than others, and may even involve students in helping to decide which skills they most need to develop.

Finally, perhaps the most important thing that flipping the order of my survey did was to teach me what I really wanted my survey to do. In the end I learned that rearranging the chronological order of the survey would not, all by itself, increase student engagement or improve their historical thinking skills. To do the latter two things, I had to part more decisively with the “coverage” ideal that animates many introductory history surveys.

A survey that aims at coverage of events in reverse-chronological order will not look that different from a survey that aims at coverage in chronological order. Many history teachers, whether for reasons within or beyond their control, will undoubtedly remain wedded on some level to a coverage ideal in the survey. But divorcing my course from that aspiration, and designing it instead around historical thinking, authentic assignments, and the present-day implications of the past, has paid dividends. Looking back on what I’ve learned so far, I’m looking forward to trying again.

Photo Credit: Flickr / romancing_the_road

Notes

-

“Thinking,” in T. Mills Kelly, Teaching History in the Digital Age (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013), link. ↩

-

Before beginning this weekly structure, we first did some varied readings on the history of gay and lesbian civil rights movements, since many of the big questions students had generated concerned this topic. ↩

-

I think I got the framing of history teaching as a kind of “coaching” from Sam Wineburg’s book, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts, though I’ve seen it used so frequently in the scholarship on teaching and learning history that my debt may be to a more diffuse group. ↩

-

Only twenty-seven students were enrolled in the class, so this was a high response rate. ↩